By Autumn Young

As fall approaches things are changing color on the Bluffton University campus – and it’s not just the leaves. The Little Riley Creek has turned a murky green over the last two weeks, thanks to a potentially dangerous bloom of blue-green algae.

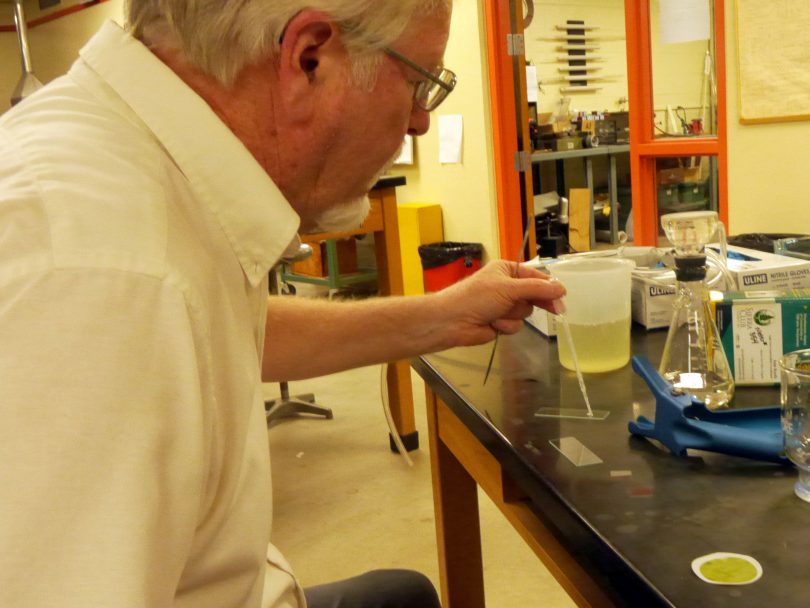

Algal blooms are powered by a potent mixture of warm, shallow water, sunlight and phosphorus – three things that have been abundant so far this semester. However, many algae species can flourish under those conditions, not all of them dangerous. To find out the exact cause of the Riley’s unnatural color, Dr. Robert Antibus, Biology department chair at Bluffton, took a water sample to analyze in Shoker Science Center.

Biology Department Chair Robert Antibus analyzes a water sample taken from the Little Riley Creek during its recent algal bloom. Photo by Autumn Young

After examining the Riley water in the lab, Antibus identified the bloom as blue-green algae—otherwise known as cyanobacteria. It is the same bacteria that left more than 100,000 people without potable water in the Toledo area last year.

“I would not recommend students go into the Riley during this bloom, to be on the safe side,” Antibus said. “You wouldn’t want to accidentally ingest any of the toxins that are likely being produced.”

The bloom has the potential to produce toxins that cause diarrhea, vomiting and liver-function problems, but Antibus noted that further analysis would be needed to determine exactly how high the levels of toxins are in the creek, and what sort of toxins are being produced.

“Overall, at this point you just want to exercise caution,” said Antibus.

People aren’t the only ones affected by the blooms. The algal blooms change stream and lake ecology, frequently killing aquatic plants and fish by absorbing sunlight and altering oxygen levels—causing environmental and recreational problems wherever the blooms appear.

Water in the Little Riley Creek has turned a murky green color in the last two weeks, thanks to a potentially dangerous bloom of blue-green algae. Photo by Autumn Young

“Agriculture is a major contributor to this problem,” said Caleb Halfhill, a junior biology and chemistry major. “Farmers use phosphorus to grow crops, and that runs off into our water, especially during years with a lot of rain, like the one we just had.”

Halfhill spent the summer working under a United States Department of Agriculture grant to find sustainable ways to grow corn.

“The problem we have now, is that everybody thinks that if they add just a bit more phosphorus, it will improve their yields and won’t matter in the long run,” Halfhill said. “But everyone does it and suddenly we have a problem. The scientists I worked with this summer, they don’t want people to stop growing corn. They just want to find a way to work with farmers so we can all continue to use our resources.”

Luckily for Bluffton, the Riley’s color change isn’t here to stay.

“As temperatures drop the bloom is going to die down and things will settle back towards normal,” Antibus said.

Algal blooms have the potential to change stream and lake ecology and may kill aquatic plants and fish. According to Biology Department Chair Robert Antibus, further analysis is needed to determine exactly how high the levels of toxins are in the creek.