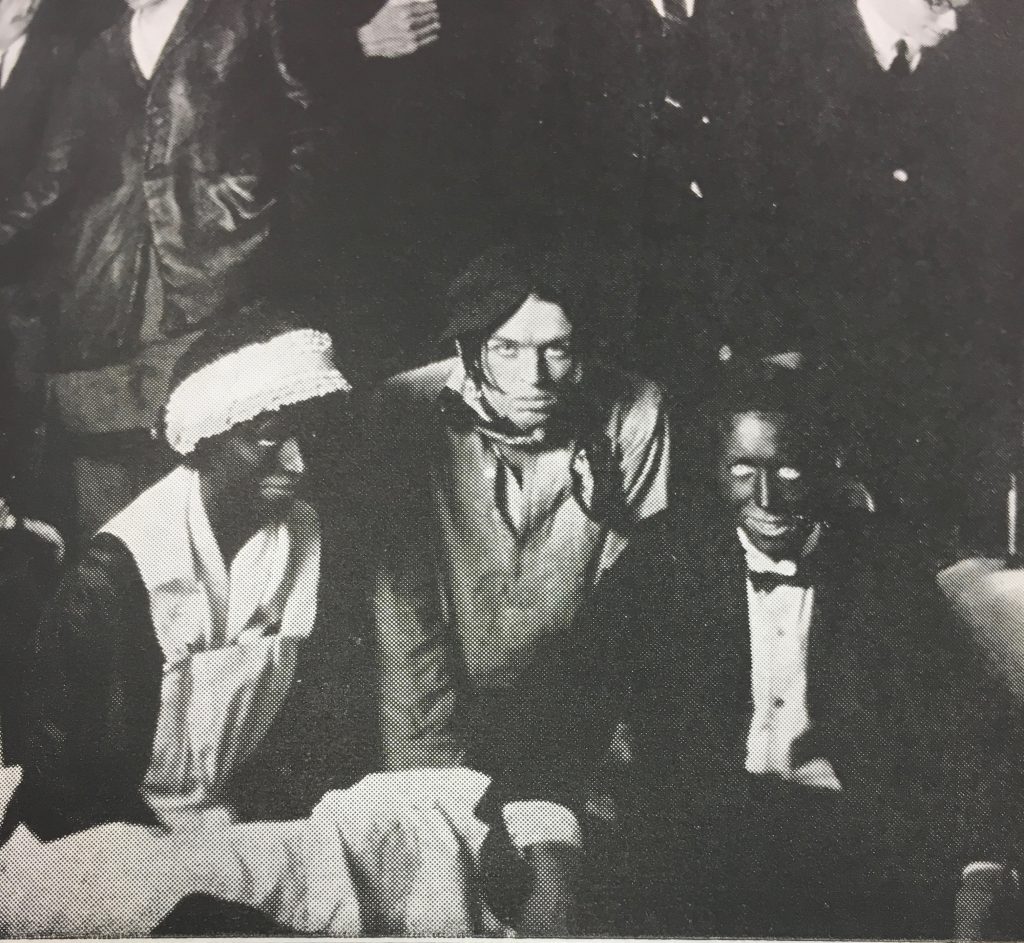

Editor’s note: some of the images accompanying this post contain sensitive material that many may consider offensive.

Bluffton University yearbooks from 1924 and 1930 include images of students wearing blackface, and this should come as no surprise.

This is not an isolated abnormality—it is the reality of colleges and universities across the nation.

Earlier this month, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam admitted to wearing blackface after an image from his 1984 Eastern Virginia Medical School yearbook went viral. The photograph in question shows two men—one in blackface and one dressed in Ku Klux Klan attire. While Northam denied being either man in the yearbook photo at one point, he later admitted to wearing blackface on a separate occasion to dress up as Michael Jackson.

Soon after the Virginia scandal broke, hundreds of similar yearbook images began to surface at universities across the country, representing a long and distressing history of racism on college campuses.

Needless to say, blackface is not a uniquely Bluffton problem, though it’s a problem Bluffton must confront, too.

Our geographic location does not exempt us, nor does our position as part of the Anabaptist peace church tradition absolve us from the deeply troubling history of racism that pervades higher education.

The Wit found yearbook evidence of blackface in theatrical performances in 1924 and 1930, and more than six instances of offensive portrayals of Asian peoples and culture in the latter half of the 20th century.

By bringing these images to light, The Wit does not seek to cause a spectacle, but to issue a challenge. It’s not about disgracing the institution we represent or the alumni involved—it’s about grappling with a disgraceful facet of Bluffton’s legacy and culture. It’s about reconciliation.

These portrayals are demeaning and dehumanizing. They make a caricature out of people of color. For far too long, actions like these have perpetuated dangerous, racist stereotypes.

Blackface has its roots in the early 19th century American tradition of minstrel shows, or minstrelsy. The minstrel show was a popular theatrical entertainment form that involved white performers darkening their faces and imitating enslaved Africans on Southern plantations, often characterizing black men and women as lazy, ignorant or hypersexual. Moving into the following centuries, blackface persisted and evolved as entertainment.

Blackface in a theatrical production in 1924. Photo of yearbook image taken by Hannah Conklin

Blackface in a theatrical production in 1930.

Photo of yearbook image taken by Hannah Conklin

It is not surprising, then, that Bluffton’s recorded blackface incidents occurred within the context of theatrical productions. While this provides context to the behavior, it does not excuse it.

Racism doesn’t just look like the donning of KKK hoods and waving Confederate flags—it manifests in mimicry and mocking, too. It manifests in college students “just messing around.”

Further, privilege is not only revealed in the unequal distribution of opportunities—it is made plain in the ability to make a joke or to turn a blind eye to discrimination.

Think about this: Where have our jokes and “harmless fun” built barriers instead of tearing them down? When have our “traditions” robbed others of their dignity and humanity rather than affirming their inherent value?

To admit blackface is a part of our institution’s history we’re not proud of only scratches the surface.

We must acknowledge the way white privilege continues to be a marginalizing force and set a precedent that racism has no place on our campus. We must listen to the voices of students and alumni of color. We must critically examine what behaviors persist on our campus today that might bring shame to future generations. We must be willing to see the ugliness of racism and admit when we are wrong.

None of us can completely undo the great harm done by institutional racism at Bluffton or anywhere else. However, we must take responsibility for actions inconsistent with our community of respect with the aim of dismantling systems of privilege that persist today.

Bluffton University is an institution I love and believe in, and I have faith we can do better. We must do better.

When defenses run high, may we confess our transgressions with grieving and open hearts.

Where lasting harm has been inflicted, may we earnestly seek to make amends and move forward in pursuit of justice.

When mere apologies are insufficient, may we fix our minds on the “purposes of God’s universal kingdom” and allow our actions to produce lasting restoration and transformation.

Hannah Conklin

The Witmarsum 2018-19 managing editor

Editor’s note:

The Witmarsum has committed to not publish the name(s) of photographed alumni or use the images in its other content distribution platforms that lack opportunity for contextual explanation. We recognize these images are not representative of Bluffton University’s Community of Respect, but determined there was value in providing readers an opportunity to verify the accuracy of the author’s words.